Sebastian Münster

Sebastian Münster (20 January 1488 – 26 May 1552), was a German cartographer, cosmographer, and a Hebrew scholar.

Sebastian Münster (20 January 1488 – 26 May 1552), was a German cartographer, cosmographer, and a Hebrew scholar.

He was born in Niederingelheim, near the city of Mainz, where in the 1460s, Johannes Gutenberg had invented printing from movable metal types.

In 1505, Münster became a Franciscan monk and studied philosophy and theology at the university of the order in Heidelberg. In 1507, he continued his education in Löwen, where he studied mathematics, geography, and astronomy.

After transferring to Freiburg, he also began studying Hebrew, which he continued after entering the St. Katharina monastery in Rouffach/Alsace in 1509 to study under Konrad Pellikan, a prominent German humanist. Beyond theology, Pellikan was a teacher of Hebrew, Greek, mathematics and cosmography and Münster became interested in these subjects. In 1511, when Pellikan moved to Pforzheim, Münster duly followed him.

In 1512, Sebastian Münster was ordained as a priest in Pforzheim. From 1514 to 1518, he taught as a lecturer of philosophy and theology at the university of his order in Tübingen, and conducted astronomical, mathematical, and geographical studies.

His most important teacher was Johannes Stöffler (1452-1531). After Münster moved to Basel in 1518, he published his first text, a survey of Hebrew grammar, "Epitome Hebraicae Grammaticae", which was one of the first-ever language books on Hebrew published in Germany.

From 1521 to 1529, Münster worked and taught in Heidelberg, published numerous Hebrew texts, and wrote the first books ever published in Germany in Aramaic. His permanent cosmographical interest is reflected by his lectures at the university and his published map of Germany (Oppelheim,1525), as well as his treatise on sundials (Erklerung des newen Instrument der Sunnen, 1528).

As a Franciscan monk, he subsequently became friends with Martin Luther. In 1529, Sebastian Münster converted to the Reformation and took over the chair of Hebrew at the University of Basel, where the Reformation had just been established.

A little later, he married Ana Selber, the widow of his book printer, Münster's stepson Heinrich Petri, from then on, he published most of his books. In 1534-1535, Sebastian Münster finally published his main work in Hebrew, which met with international acclaim: a two-volume edition of the Old Testament "Biblia Hebraica" with a Latin translation and annotations.

In the May of 1552, Münster died of plague in Basle and was buried in there, but his works remained influential in the period of the next generation of great modern map makers.

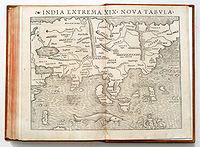

Geographia universalis vetus et nova

The "Geographia universalis" first printed in 1540 was one of the most reliable editions of Ptolemy. Münster used a Greek manuscript for his translation and corrected many misinterpretations of the earlier Latin text by Willibald Pirckheimer with corrections of 1535 by Servetus. Along with the traditional 1+26 Ptolemaic maps the book included 21 modern maps. The new maps marked the development of regional cartography in Central Europe. All the maps were printed from woodblocks, made by the Basler artist Conrad Schnitt. The geographical names and map inscriptions were printed from stereotypes and/or from set metal types in the case of titles outside the upper border, and the descriptive text found in panels on the verso side of the maps.

The "Geographia universalis" first printed in 1540 was one of the most reliable editions of Ptolemy. Münster used a Greek manuscript for his translation and corrected many misinterpretations of the earlier Latin text by Willibald Pirckheimer with corrections of 1535 by Servetus. Along with the traditional 1+26 Ptolemaic maps the book included 21 modern maps. The new maps marked the development of regional cartography in Central Europe. All the maps were printed from woodblocks, made by the Basler artist Conrad Schnitt. The geographical names and map inscriptions were printed from stereotypes and/or from set metal types in the case of titles outside the upper border, and the descriptive text found in panels on the verso side of the maps.

It was Münster, who devoted a map for each continent in his book and this invention was followed later by Ortelius and the modern atlas publishers. The map devoted to America is one of the most famous and important of the sixteenth century.

When one considers that Munster was working only some 50 years or so after Columbus discovered America, the fact that there is any real substance to some of the maps is quite amazing.

The woodcut borders surrounding the type on the verso of the maps are largely the work of Hans Holbein.

The Geographia was a very successful product: two year after the first edition it was reprinted in 1542, then again in 1545 and 1552.

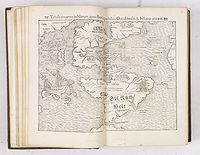

Münster's second important work was the "Cosmographia" (Basel, 1544), a geographical and historical description of the world with special attention to Germany, which initially included 471 woodcuts and 26 maps in 6 volumes. This work was based on the work of more than two decades and several research trips.

"Cosmographia" was translated into various languages, reprinted almost 50 times and extended by more than 900 woodcuts. By 1628, 21 editions had been published in Germany alone. The work is regarded as one of the most important books of the 16th century and is almost the only reason for Münster's lasting fame.

One of the most popular treatises of the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries,

the Cosmographia reached a total of forty-six editions in six languages by 1650, each incorporating additions and revisions. In its completion, which occupied him for fifteen years, Münster received the assistance of more than one hundred and twenty collaborators, who provided him with the most up-to-date information relating to the towns and places described.

The most valuable sections scientifically speaking are those which deal with Germany and Central Europe. In addressing his German colleagues for information, Münster outlined fairly detailed directions, devising the first known example of a simple plane-table survey. Included are separate sections on the Holy Land, Africa, and Asia, while contained on pages 1099-1112 under the title "De Novis Insulis, quomodo, quando & per quem illae inventae sint", is a description of America, with relations of the voyages and discoveries of the early explorers, Columbus, Vespucci, Magellan, &c.

The Cosmographia is profusely illustrated with woodcut town plans and views (many double-page), including some of the earliest published large-scale views of European cities, portraits, coats of arms, costumes, customs, mining and other activities, cannibalism, natural history subjects, &c., by Hans Holbein, Urs Graf, Hans Rudolph Manuel Deutsch, David Kandel, and other artists.

The fourteen double-page woodcut maps, drawn by Münster himself, include two world maps, on the first of which

Terra Florida (North America) and America vel Brasilii ins. (South America) are named, and the first general maps of the continents, Europe, Asia, Africa, and America.

The Tabula novarum insularum is “the first map of the two American continents showing continuity between North and South America and no connection with any other landmass.” (Schwartz & Ehrenberg, The Mapping of America, pp. 43-45, Plate 78).

The Tabula novarum insularum is “the first map of the two American continents showing continuity between North and South America and no connection with any other landmass.” (Schwartz & Ehrenberg, The Mapping of America, pp. 43-45, Plate 78).

All of the maps had originally appeared in Münster’s 1540 edition of Ptolemy, except the modern world map was re-cut with several changes by David Kandel for the 1550 editions of the Cosmographiae.

As an

exhibition of the progress of geographical discovery, Munster’s Cosmographie is indispensable. It is interesting both for the informative text and its profusion of curious and inspired woodcuts. This work combines medieval allegory and superstition with modern knowledge and thought. It has been said that the Cosmographie of Sebastian Munster “will remain an important source for the history of the civilization of the period.” -- The World Encompassed, 272.

References : Adams M1910. Alden 554/47. Borba de Moraes II 90. BM STC German p. 633. Burmeister, Münster, 89. JCB I p. 183. Ruland, Imago Mundi XVI pp. 87-88.

Sabin 51381. Bell M523, Harrisse 300, The World Encompassed, 272. National Maritime Museum, Atlases, 465 (1550 edn.). Nordenskiöld Collection II 155 (1552 edn.).

Nordenskiöld, Facsimile Atlas, pp. 108-09 & 24. Shirley, The Mapping of the World, 92 (modern world) & 76 (ancient world).