Civitates Orbis Terrarum

The Civitates Orbis Terrarum (Atlas of Cities of the World) by Hogenberg was the second oldest printed atlas in the history of world cartography, and the first atlas of towns.

Its principal creators and authors were the theologian and editor Georg Braun, the most important engraver and publisher Frans Hogenberg, the engraver Simon van den Neuvel,

the artist and draftsman Georg (Joris) Hoefnagel, the topographer Jacob van Deventer and others.

Although published outside the Netherlands, the Civitates is, nevertheless, one of the best examples of the work of the Antwerp school of cartographers.

Some of the key figures in the school were Abraham Ortelius, Gerardus Mercator, and a number of other geographers. The Civitates reflects the Flemish style of engraving, which was typical of Dutch atlases of the period. In addition, the correspondence between Braun, Hogenberg,

and Ortelius contains clear indications that the idea to create the atlas was formulated by them in Antwerp.

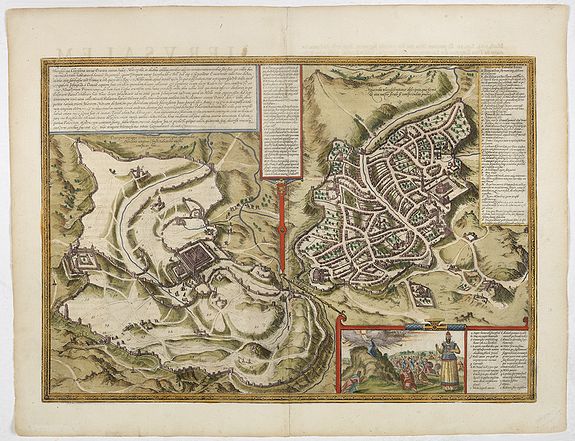

The more than 500 maps contained in the atlas represent an entire era in the history of town mapping. Six volumes of the atlas were published between 1572 and 1617. In order to obtain the originals for his work, Braun corresponded extensively with map sellers and scholars from different cities and countries. Additionally, the authors conducted their own investigations.

However, these were not true geodetic surveys, but detailed on-location drawings of panoramic views of the towns made from some high point. Most of the engravings that decorate the Civitates from its first volume to its last were made from such drawings by Georg Hoefnagel. Hoefnagel drew images of many towns in France, Italy, England, and Spain.

He and his son Jacob subsequently created representations of Austrian and Hungarian towns for the Civitates. Besides such overview plans, the atlas includes also more detailed maps based on topographic surveys, and particularly the surveys of Jacob van Deventer (15??-1575). Correspondingly, the maps show the systematic structure of the towns' building up with the perspective representation of various quarters and individual buildings.

The town is usually placed in the background, while in the foreground is the description of its surrounding countryside and the depictions of typical inhabitants of the town in every detail.

These visual representations of people served not only to augment the contents of the maps but also for another purpose. The pages of Braun and Hogenberg's Civitates were illustrated with figures of local inhabitants to prevent the maps from being used by the Turks for military goals since Islam forbids images of humans.

Of the total number of towns, only a couple of dozen are located outside Europe: in Asia, Africa, and South America. This is evidence of extremely limited cartographic knowledge of the world, due to the insufficient development of science and practices of mapmaking in the second half of the sixth century. At the same time, it is impossible not to be astonished at the huge quantity - by the standards of the time - of material included in the atlas.

Braun and Hogenberg's Civitates was an enormous success. It was republished and supplemented by new sections many times. Maps contained in it became exemplary; they

were frequently reproduced in a smaller format by other publishers as illustrations for books and maps.

Braun and Hogenberg's Civitates was an enormous success. It was republished and supplemented by new sections many times. Maps contained in it became exemplary; they

were frequently reproduced in a smaller format by other publishers as illustrations for books and maps.

After Franz Hogenberg's death, the typographic plates for the atlas remained in Cologne, in the possession of Abraham Hogenberg. When Abraham died in 1653, his heirs evidently sold them to Johannes Janssonius, an active and skilled publisher of books and atlases in Amsterdam. In 1657, Janssonius issued the atlas in eight volumes in a completely revised edition, with illustrations arranged by country. A large number of quite new engravings were added to it, while outdated prints were omitted. Following Janssonius's death in 1664, the engravings became the property of his grandson Johannes Janssonius van Waesberge, who used some of them to compile his own atlas, which appeared in 1682.

In 1694, van Waesberge's copper plates and equipment were purchased at auction by the energetic Amsterdam publisher Frederick de Wit, who was well-known for his numerous maps and atlases. De Wit organized a new edition, which was also enriched with new engravings.

After de Wit's time, at the turn of the eighteenth century, the copper plates for the atlas passed into the hand of the publisher Pieter van der Aa (1659 - 1733). He acquired them in Leyden and used for an atlas which came out in 1729. This publication included a diverse mixture of engraving from the sixteenth to eighteenth centuries.

After van der Aa, ownership of town maps with the publisher's imprint of de Wit passed to the publishing house of Covens and Mortier. The multiple reproductions by various publishers of these 16th-century perspective views and maps over centuries can be explained by their rich historical and geographical content.

At the same time, it is necessary to say that there is no atlas of the world's cities in the history of global cartography to equal the Civitates Orbis Terrarum in its size and fullness.

In addition to its historical, geographical, and cartographic significance, the Civitates is also of great artistic value. That is why, up until now, the town maps, contained in the atlas, have adorned the most exquisite interiors and attracted the attention not only of specialists in the field but of all admirers of fine art.