The mapping of the Low Counties

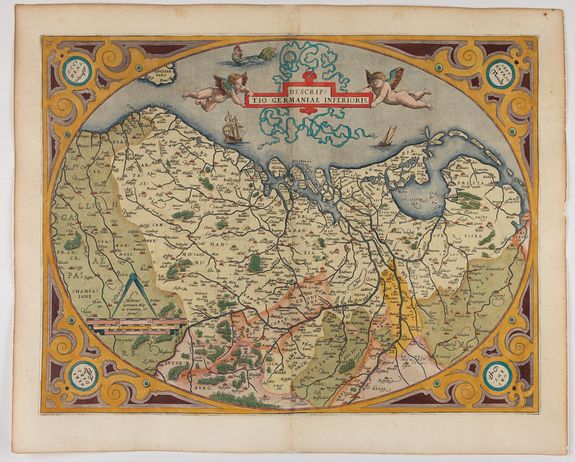

From the late sixteenth to the eighteenth century, Dutch mapmaking set the global standard for accuracy, beauty, and commercial reach. Amsterdam became Europe’s cartographic capital, where engravers, publishers, and sailors fed a thriving market for atlases and sea charts. Early innovators such as Gerard Mercator and Abraham Ortelius shaped conventions, but Dutch firms—above all the Blaeu, Hondius, and Janssonius houses—popularized them through copperplate engraving, meticulous hand‑coloring, and bold typography. Navigation drove demand.

The Dutch East India Company (VOC) and West India Company (WIC) gathered observations from worldwide voyages; some charts were guarded as trade secrets, while others appeared in splendid atlases, culminating in Blaeu’s monumental Atlas Maior (1662).

Techniques advanced as well. Willebrord Snellius’s triangulation refined surveys at home; rhumb lines, soundings, and coastal profiles improved pilot guides following Waghenaer’s seminal Spieghel der Zeevaerdt.

Dutch wall maps and globes adorned town halls and merchants’ houses, projecting power and curiosity.

By the eighteenth century, competition from French academies and British naval charting, plus shifting trade patterns, eroded Dutch dominance. Yet the Dutch Golden Age legacy endured: a synthesis of science, commerce, and artistry that transformed maps from practical tools into cultural icons. Its influence still shapes mapping, design, and historical imagination.