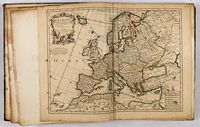

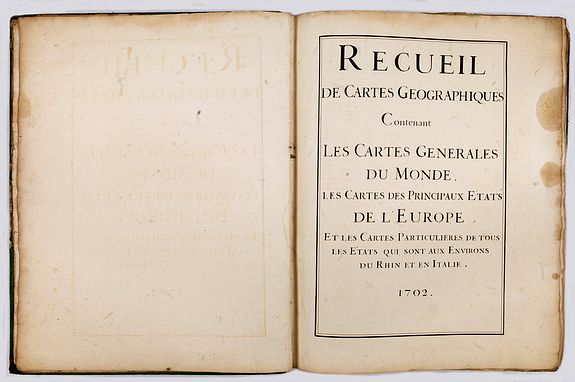

Recueil de cartes géographiques contenant les cartes générales du monde

His first Atlas, published in the year de l'Isle became the geographer to the French Academy of Sciences (1702).

DE L'ISLE - (Atlas). Recueil de cartes géographiques contenant les cartes générales du monde, les cartes des principaux États de l'Europe et les cartes particulières de tous les états qui sont aux environs du Rhin et en Italie."

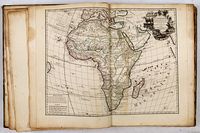

Large folio including 69 maps by DE L'ISLE (Guillaume, SANSON (Nicolas), JAILLOT (Alexis Hubert), or after DE FER (Nicolas), NOLIN (Jean-Baptiste), SENGRE (Henry), COROLNELLI (P.). The title page is dated 1702. (The year de l'Isle became the geographer to the French Academy of Sciences)

This is the earliest recorded edition of de L'Isle's atlas, with the world, four continents, and a map of England by de L'Isle bearing the "Rue des Canettes imprint.

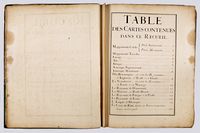

The atlas has a simple title page, carrying the date 1702 and two pages of an Index.

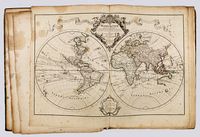

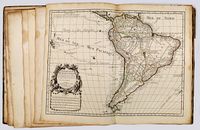

The atlas contains a World map in double hemispheres. 4 continent maps (with America presented in a north and south part) all with the earliest "rue de Canettes address and dated 1700, a celestial chart and followed by maps of European countries.

The maps are numbered in an 18th-century hand, in the outer right margin.

This item has been Sold

De l'Isle is essential as the first "scientific" cartographer, incorporating the latest information on exploration and topography into his maps. De L'Isle was a much esteemed figure who, after being tutored by the great Jean-Dominique Cassini, became the geographer to the French Academy of Sciences in 1702, and then 'Premier Géographe' to Louis XV in 1718.

Rodney Shirley notes that "De L'Isle's work is distinguished by its scientific basis, the minute care taken in all departments, constant revision, and personal integrity".

L’Isle also played a prominent part in the recalculation of latitude and longitude, based on the most recent celestial observations. His major contribution was in collating and incorporating this latitudinal and longitudinal information in his maps, setting a new standard of accuracy, quickly followed by many of his contemporaries.

His maps of America contain many innovations: discarding the fallacy of California as an island, the first naming of Texas, the first correct delineation of the Mississippi Valley, and the first correct longitudes of America. Lloyd Brown states that DeLisle "undertook a complete reform of a system of geography that had been in force since the second century, and by the time he was twenty-five, he had nearly accomplished his purpose."

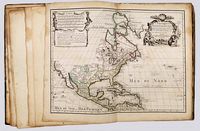

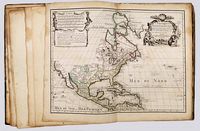

L'Amerique Septentrionale Dressee sur les Observations de Mrs. de l'Academie Royale des Sciences . . . Rue des Canettes prez de St. Sulspice Avec Privilege du Roy pour 20. ans 1700.

L'Amerique Septentrionale Dressee sur les Observations de Mrs. de l'Academie Royale des Sciences . . . Rue des Canettes prez de St. Sulspice Avec Privilege du Roy pour 20. ans 1700.

One of the most essential maps in this atlas is De l’Isle’s foundational map of North America, with milestone depictions of the Mapping of the Mississippi and California - here in a first obtainable state.

This highly important map of North America is the first to locate the mouth of the Mississippi accurately and to depict California as a peninsula.

De L'Isle's map of North America is a widely celebrated cartographic landmark. De L'Isle had access to the latest information from French explorers in the New World, when the French dominated exploration of the continent's interior. This meant that De L'Isle's maps were invariably updated and innovative in their content.

While his first regional maps did not appear until 1703 (Carte du Mexique et de la Floride... and Carte du Canada ou de la Nouvelle France) and 1718 (Carte de la Louisiane et du cours de Mississipi.... ), this map represents De L'Isle's first work on America. It was highly influential to other maps of the period, both for what it includes and as a snapshot of the knowledge available to De L'Isle in the three years immediately before he issued the regional maps.

The map is highly detailed, though areas lacking information are boldly left blank. In addition to settlements, rivers, forts, and mountains, De L’Isle has included numerous notes about geographic features and local peoples. For example, in the southwest, the Apaches are described as “vaqueros”, or skilled horsemen, as well as vagabonds.

The Great Lakes, based on Coronelli, show the French strongholds at Tadoussac, Quebec; Fort Sorel; Montreal; and Fort Frontenac. The English settlements are located east of the Alleghenies, with Fort and River Kinibeki as the border between New England and Acadia.

The Mississippi River Valley and the states of this map

This is a map of firsts, including being the first to show the Sargasso Sea (Mer de Sargasse). The most significant first, however, is the earliest correct placement of the mouth of the Mississippi River on a printed map.

In the previous cartobibliography, the map considered the first state includes the cartographer's address as "Rue de Canettes" in the cartouche; the second state has the address of “Quai de l’Horloge.” An article in the Map Collector (Issue 26, pp. 2-6, March 1984) by Schwartz and Taliaferro describes a copy located in Austria of an earlier state in which the mouth of the Mississippi River is shown in Texas, rather than, as on the later states, in Louisiana, slightly west of longitude 280º. That earlier state is known in only a very few examples.

The lower portion of the Mississippi River is angled differently from Cassini’s efforts. Farther upriver, this is the first map to show the Wabash as a tributary of the Ohio River. This is also one of the earliest maps to show the Louisiana expeditions led by Pierre Le Moyne d’Iberville (1698-1699).

Early in his career, D’Iberville explored Hudson Bay and harassed the Hudson’s Bay Company on behalf of the Compagnie du Nord. After the Sieur de la Salle travelled from the Great Lakes to the Gulf of Mexico via the Mississippi River in 1682, d’Iberville was tasked by the Minister for Naval Affairs and Colonies, Pontchartrain, to locate the mouth of the river.

D’Iberville left Brest in October 1698 with four ships. He sailed along the Gulf Coast, past the new Spanish fortifications at Pensacola, shown on this map, and arrived at the Birdfoot Delta in March 1699. Thanks to native informants, he found that this was indeed the river he was looking for.

D’Iberville set out again the following year. He sailed this time to Biloxi, here marked: F. des Bilocchy. He also returned in 1701, after this map was initially published, to build a fort at Mobile (here Mobila). In 1718, his brother, Jean-Baptiste Le Moyne de Bienville founded New Orleans.

The island of California

One of the most notable aspects of De L'Isle's map is that it is considered the first map to depict California as a peninsula. However, it is more accurate to say that this map shows De L’Isle’s evolving thoughts on California. Careful examination shows that the Californie and Nouveau Mexique do not meet, and the coast north of C. Mendocin is left blank. Such calculated, conservative depictions highlight De L’Isle’s skill and mark this map as a crucial linchpin in the reevaluation of California's geography from the late seventeenth to mid-eighteenth centuries.

From its first portrayal on a printed map by Diego Gutiérrez, in 1562, California was shown as part of North America by mapmakers, including Gerardus Mercator and Ortelius. In the 1620s, however, it began to appear as an island in several sources, including Samuel Purchas’ Hakluytus Posthumus or Purchas his Pilgrimes (1625).

This was most likely the result of a reading of the travel account of Sebastian Vizcaino, who had been sent north up the shore of California in 1602. A Carmelite friar who accompanied him described the land as an island and sketched maps to that effect. Usually, this information would have been reviewed and locked in the Spanish repository, the Casa de la Contractación, but the Dutch captured the ship carrying the map and other Vizcaino documents. Prominent practitioners like John Speed, Jans Jansson, and Nicolas Sanson adopted the new island, and the practice became commonplace. Even after Father Eusebio Kino published a map based on his travels refuting the claim (Paris, 1705), the island remained a fixture until the mid-eighteenth century.

This does not imply that all mapmakers blindly accepted the convention. In 1700, roughly the same time this map was initially produced, De L’Isle discussed “whether California is an Island or a part of the continent” with J. D. Cassini; the letter was published in 1715. After reviewing all the available literature in Paris, De L’Isle concluded that the captured Spanish map was not trustworthy, as other Spanish maps depicted California as a peninsula. He also cited more recent Jesuit explorations (including Kino's) that disproved the island theory.

De l'Isle concludes:

On my maps and globes, I have taken the precaution of representing the coast as cut and interrupted in this place, as much on the side of Cape Mendocino as on the side of the Red Sea. I have left in these two places as though stepping stones during an interrupted work, and I have not believed it necessary to make up any mind about a thing which is still so uncertain; therefore I have made California neither an Island nor a part of the Continent, and I will stay with this point of view until I have seen something more positive than I have seen to date. (quoted from translation in Polk, 316)

This description accurately describes California as depicted on this map and marks it as an essential declaration of De L’Isle’s broader cartographic philosophy. Later, in his map of 1722 (Carte d’Amerique dressee pour l’usage du Roy), De L’Isle would abandon the island theory entirely. However, his contemporaries and successors, including his son-in-law, Philippe Buache, remained adherents to the island depiction for some time.

Thanks to its innovation and consideration, this map was the most influential in the transition from California being an island to a peninsula in the eighteenth century. It was also visionary in its depiction of the mouth of the Mississippi, affecting general representations of the North American continent for the entirety of the eighteenth century.

References: Dora Beale Polk, The Island of California: The History of a Myth, Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1995; Ernest J. Burus, S. J., Kino and the Cartography of Northwestern New Spain, Tuscon: Arizona Pioneers’ Historical Society, 1965; Guillaume De L’Isle, “Lettre de M. de Lisle touchant la California,” in Recueil de Voyages au Nord (Amsterdam, 1715); John Leighly, California as an Island: An Illustrated Essay (San Francisco: Book Club of California, 1972); Glen McLaughlin with Nancy H. Mayo, The Mapping of California as an Island: An Illustrated Checklist, Saratoga, CA: California Map Society, 1995; Burden, Mapping of North America II, map 761. KAP.

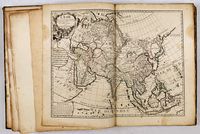

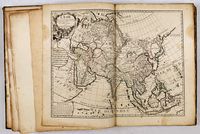

L'ASIE Dressée sur les Observations de l'Académie Royale des Sciences et quelques autres, et sur les mémoires les plus recens.... Rue des Canettes prez de St. Sulspice Avec Privilege du Roy pour 20. ans 1700. An important and rare map of Asia, issued by Guillaume Delisle and with 3 nice decorative cartouches, engraved by N. Guerard. It includes the East Indies and the tip of New Guinea. Japan is connected to the mainland by a country identified as Terra Yeco (Hokkaido). Showing "Mer Oriental".

L'ASIE Dressée sur les Observations de l'Académie Royale des Sciences et quelques autres, et sur les mémoires les plus recens.... Rue des Canettes prez de St. Sulspice Avec Privilege du Roy pour 20. ans 1700. An important and rare map of Asia, issued by Guillaume Delisle and with 3 nice decorative cartouches, engraved by N. Guerard. It includes the East Indies and the tip of New Guinea. Japan is connected to the mainland by a country identified as Terra Yeco (Hokkaido). Showing "Mer Oriental".

At the northwest is the fictional ‘Terra de la Compagnie’, Korea is shown as a peninsula. The coastline of north-eastern Siberia between Novaya Zemlya and Terre de Yeco is left blank.

The map is very interesting for the use of 'Mer Orientale', the sea between Korea and Japan. The map also shows Singapore and Saicapura. The map is dated 1700.

De L'Isle's map of Asia would become the source map for several other contemporary mapmakers, including J.B. Homann, Covens & Mortier, Nolin, De Fer and others.

Another essential map is his world map and proved to be one of the most influential world maps of its time, and is present here in the rare first state, also with the address "Rue des Canettes".

In this map of the world, De l'Isle was among the first cartographers to re-establish California's proper form as a peninsula, to give more or less accurate configurations to all five Great Lakes, and to show the full extent of the Mississippi. He was also one of the first to correct the attenuated form of the Mediterranean Sea. In fusing New Guinea and Australia, he followed William Dampier's presumed personal survey. Still, he resisted the temptation to join Tasmania and New Zealand to Australia, an error soon to be popular. Curiously, the tip of South America is depicted as curving sharply into the Pacific, a detail conspicuously omitted in subsequent states of the map. The map also features the tracks of essential circumnavigators, including Magellan, Mendaña, Dampier, Van Noort, Le Maire & Schouten, and the antipodean tracks of Abel Tasman. Shirley The Mapping of the World: Early Printed World Maps 1472-1700, 603, plate 416; Wagner Cartography of the Pacific Northwest, 461.