Venice

Brought to Florence about 1400 from Byzantium, the eight books of Ptolemy's Geographia, seven of which consist mainly of locational coordinates for toponyms across the known world, were translated into Latin by 1410 and published for the first time in Venice in 1475.

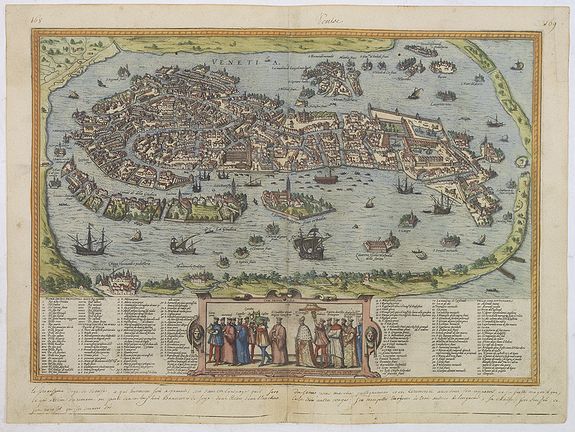

It is easy to understand why mapping should hold a particularly significant place in the daily life of early modern Venice. A commercial center of the first order that depended on maritime trade for its economic life and boasted the largest merchant fleet in Europe had an enduring need for accurate, up-to-date charts of its trading sphere. From the late thirteenth century, these were produced in Genoa and later in Venice, where Pietro Vesconte was recorded as the first professional cartographer in the early fourteenth century.

The world map produced in Fra Mauro's workshop on Murano dated 26 August 1460 represents the culmination of a great medieval tradition of mappae mundi. These maps vary significantly in form and content. They could be accreting new knowledge gained from travelers and navigational charts to their basic synthesis of Classical and Biblical conceptions of the world.

With the Fall of Byzantium in 1453, Venice became the principal inheritor of its intellectual traditions. Venice's role as a major European publishing center in the sixteenth century and the relative freedom with which information circulated was equally significant.

Maps of Asia illustrating the Polo discoveries decorated the Sala di Scudo in the Ducal Palace on its redecoration after the fire of 1483, painted over by Giacomo Gastaldi in the later sixteenth century and again in 1762; while in 1460 the Council of Ten ordered local governors in the terraferma and Stato da Mar to have maps drawn of their areas for submission to Venice, a policy which has left some of the most sophisticated regional maps of the early Renaissance and which has prompted one writer to claim that Venice was 'the only state in fifteenth-century Europe to make regular use of maps in the government's work.

Late fifteenth-century Venice thus had a tradition of both geographic and chorographic map production upon which to draw. To this, we must add the mariners' portolan charts, many of their makers anonymous, with their increasingly accurate outline of coasts, coastal places, and dense network of navigational rhumb lines.

By the turn of the sixteenth century, map publishing in Venice was highly organized. Workshop production consisted of four functions in creating the map: compilation/design, which involved collecting information and plotting it on a plan; engraving in wood or copper; printing; and publishing. Throughout the century, it is difficult to differentiate these functions regarding the individuals involved. However, many distinct workshops can be recognized from their imprints: Camocio, Bertelli, Forlani, Pagano and Tramezzino.

Certainly, their activity meant that maps probably circulated more easily and widely in this city than any other in Europe, forming one foundation for what we may call 'cartographic literacy' among the Venetian patrician and citizen classes.

At the same time, the growing numbers of unpublished maps and disegni emerging from the demands for survey: hydrographic, military, legal and administrative further encouraged this familiarity with maps in Venice and underpinned the broader role of cartography in its sixteenth-century cultural life.