The Middle East Trade

The first was standardization of the money, the second, of weights and measures. A third was language standardization, and the fourth, standardization of commercial law.

Standardizations also improved the quality of transaction technology by shifting knowledge transmission from oral to written means. The adoption of paper over papyrus, a technological innovation, increased the supply of writing material and improved transaction technology.

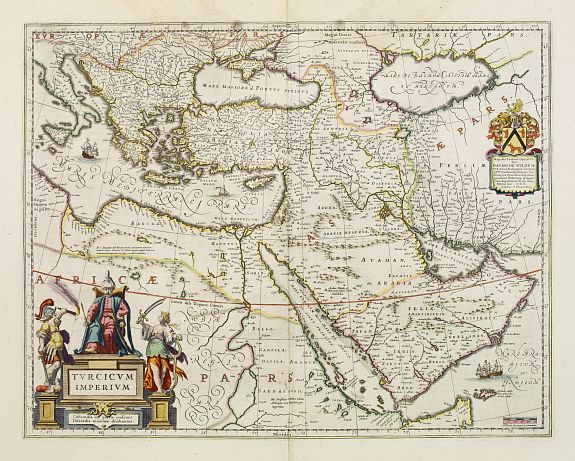

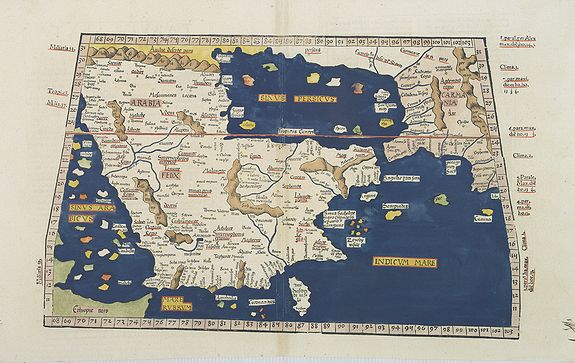

The Middle East traders are known for centuries for their Pearling Industry, Their trading of Gold and Currency, spice, weapons, textile and carpets, slaves, horses, dates, perfume, rice, sugar and tea and coffee trades.

19th Century

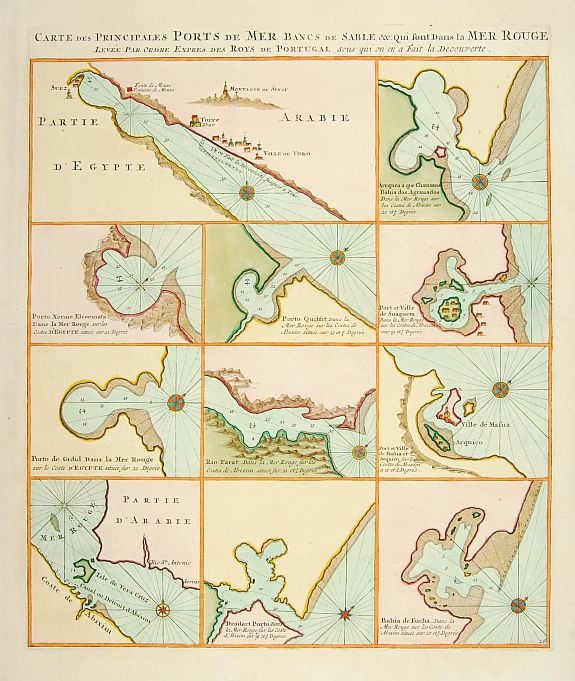

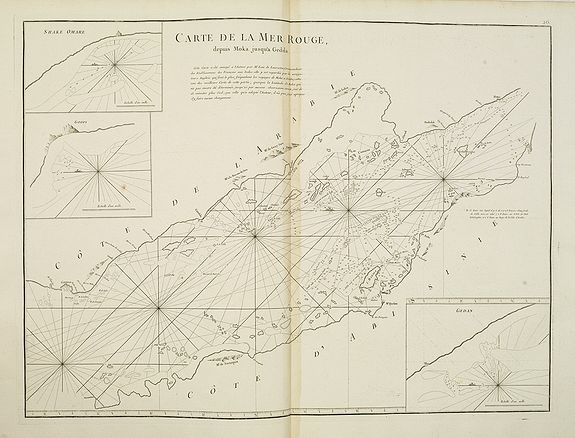

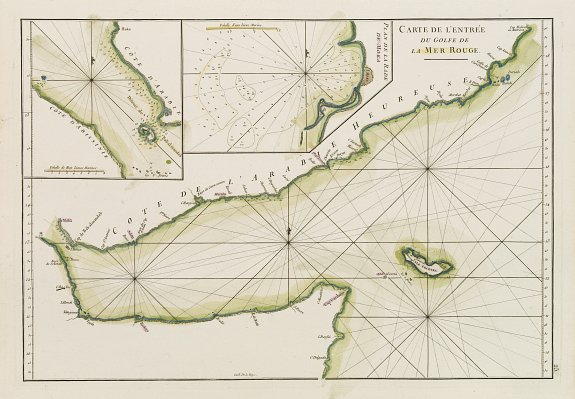

In the early 19th century, Britain emerged as the master power in the Indian Ocean and Arabian Gulf, especially after the Arab rulers of the Gulf signed the peace agreement with the British in 1820, which enabled Britain to control the trade between India and the Arabian Peninsula. The British authorities, moreover, provided local people of the Gulf with a sense of commercial security in order to enhance the regional economy. Also, in the second half of the 19th century, India became the chair of the British Viceroy, so all the British colonies and protectorates in the Arabian Gulf and Indian Ocean were ruled from India. Moreover, with the spread of steamships in the second half of the 19th century and the opening of the Suez Canal in 1869, the Arabian Gulf and Indian Ocean were re-integrated in the global economy and local products, such as pearls and dates, found their way to the markets of Europe and North America while European and American products were sold in the markets of the Gulf ports.

These changes enhanced the economic importance of India, making it the most attractive trading center in the Indian Ocean region. As a result, the trade between Arabia and India fully recovered, after it was cut with the arrival of the Portuguese colonizers in the early 16th century, and people from Central Arabia, also known as Najd, began to migrate to the Gulf ports, especially Kuwait and Bahrain. However, the Gulf ports were not the Najdis’ last trading destination. Rather, since most goods imported to the Gulf ports had come from the Indian ports, the Najdis traveled to India itself and resided in the major trading centers, such as Karachi, Bombay, and Calcutta. The Najdis associating with the Gulf ports, especially Kuwait and Bahrain, were known as ahl al-ḥaḍra or al-ḥaḍrat (people of downward). Thus, by the end of the 19th century, the Quṣmân2 (sing. Qaṣîmî, inhabitants of al-Qaṣîm, which is one of the three major districts of Najd) had established an economic network that connected their homeland, al-Qaṣîm, to many trading centers, such as Cairo, Damascus, Gaza, Jerusalem, Baghdad, Basra, Kuwait, Bahrain, al-‘Uqayr, al-Jubayl, Mecca, Madinah, Jidda, Karachi, Bombay, and Calcutta.

![14177/220:Arabic Meche [Mekka]](/images/Lgimg/14177.jpg)