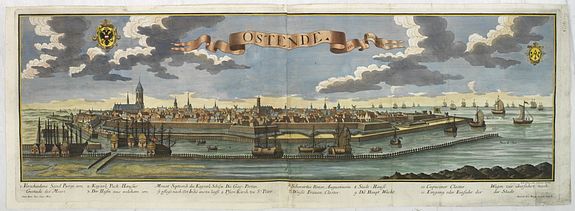

The Ostend East-India Company

The trade from Ostend in the Austrian Netherlands to Mocha, India, Bengal and China started in 1715. Some private merchants from Antwerp, Ghent, and Ostend were granted charters for the East India trade by the Austrian government, which had recently come to power in the Southern Netherlands. Between 1715 and 1723, 34

ships sailed from Ostend to China, the Malabar or Coromandel coast,

Surat, Bengal or Mocha. Those expeditions were financed by

different international syndicates composed of Flemish, English,

Dutch and French merchants and bankers. The mutual rivalry between them, however, weighed heavily on profits, leading to the founding of the Ostend East-India Company, chartered by the Austrian emperor in December 1722.

The trade from Ostend in the Austrian Netherlands to Mocha, India, Bengal and China started in 1715. Some private merchants from Antwerp, Ghent, and Ostend were granted charters for the East India trade by the Austrian government, which had recently come to power in the Southern Netherlands. Between 1715 and 1723, 34

ships sailed from Ostend to China, the Malabar or Coromandel coast,

Surat, Bengal or Mocha. Those expeditions were financed by

different international syndicates composed of Flemish, English,

Dutch and French merchants and bankers. The mutual rivalry between them, however, weighed heavily on profits, leading to the founding of the Ostend East-India Company, chartered by the Austrian emperor in December 1722.

The company's capital was fixed at 6 million guilders, divided into 6,000 shares of 1,000 guilders each. It was mainly supplied by the moneyed inhabitants of Antwerp and Ghent. The directors were chosen from the wealthy and skilled merchants or bankers who had been involved in the private expeditions. The company also possessed two factories: Cabelon on the Coromandel coast and Banquibazar in Bengal.

Between 1724 and 1732, 21 company vessels were sent out, mainly to Canton in China and to Bengal. Thanks to the rise in tea prices, high profits were made in the China trade. This was a thorn in the side of the older rival companies, such as the Dutch VOC, the English EIC and the French CFT. They refused to acknowledge the Austrian emperor's right to found an East-India company in the Southern Netherlands and considered the Ostenders interlopers. International political pressure was put on the emperor and he finally capitulated.

In May 1727, the company's charter was suspended for seven years, and in March 1731, the Second Treaty of Vienna ordered its definitive abolition. The flourishing Ostend Company had been sacrificed to the interests of the Austrian dynasty. Between 1728 and 1731 a small number of illegal expeditions were organized under borrowed flags, but the very last ships sailing for the company were the two "permission-vessels" that left in 1732 and were a concession made in the second treaty of Vienna.

Only a few documents are left because the municipal archives of Ostend were lost during the Second World War.

The ships used for the East India trade were generally large three-masters of the frigate-type, heavily armed and measuring several hundred tons. The vessels used by the Ostenders were of the same type. Although the period of activity was rather short, there was already a clear tendency to use larger ships.

The first ships that sailed in 1715-1717 measured only 200 to 250 tons, but the average of 22 private East-Indiamen (1715-1723) was 330 to 360 tons. The company took over some of the larger private vessels and bought a few others, second-hand ships of about 400 tons. From 1725 on, the company directors ordered new ships built in Hamburg and in Ostend. The average size of those vessels was 600 tons, raising the average for the 15 company ships from 407 to 433 tons. It was only for the illegal expeditions of 1729-1730 that the company again preferred smaller bottoms.

The small Ostend shipyards at first were not able to produce vessels of that size and so the Ostenders were obliged to look for their ships abroad. The private merchants bought them mainly in England. Of 23 private vessels, 15 came from England, against 8 from the Northern Netherlands, and the English preponderance is even greater when we consider that those 15 ships made 25 voyages between 1715 and 1723, against only 9 voyages for the 8 Dutch vessels. The English private East-Indiamen were smaller than the Dutch. The latter averaged around 390 tons, against around 320 tons for the English. This difference in size seems to have been typical for both types of ships.

The Sea Routes - Charts and

Navigators

The route the Ostend ships followed was very similar to that of

the other European companies. This is not a surprise since the

first expeditions were often organized under the command of foreign

captains and mates. These officers had already undertaken a few

voyages to the East Indies in English or French service. In this

way, Flemish officers learned to navigate safely around the Cape to

Asia.

There was also foreign influence in the sea rutters and the

charts on board. The Ostenders used a combination of Dutch, English, and French charts and sailing directions. In two journals of

private voyages data were given on the origins of the charts and on

knowledge of navigation problems. The captain of the Mochaman

Stadt Gendt (I 720) attached more value to the observations

of the English hydrographers Thornton and Seller than to the

information on the sea charts of St. Malo.

Aboard the same ship,

there was also a chart of the Dutchman Pieter Goos. When another

Mochaman, the Graaf van Lalaing (1721), called at Fayal

after six weeks of sailing from Pernambuco, the captain and the mates

started a discussion on the longitude of the Azores. They found a

difference of 7'45 min. between the dead-reckoning and an

unspecified English chart. The captain gave two possible

explanations: '... de stroom die loopt omtrent de linie

om de west oft dat de cust van Bresil 5 a 6gr. westelicker

liggen volghens de stellingh van de engelse hydrograef

edmund Halley...'.

It is remarkable that the Ostenders knew and

used Edmund Halley's theory of the variation of the compass and the isogonic lines, whereas this innovation did not find general

acceptance on board VOC ships until 1740. The tradition of

navigation with the help of foreign sea-charts and rutters

continued on the GIC ships.

The company directorate ordered all maps and navigation instruments from London and Amsterdam. From England arrived in 1723, along with East India pilots and charts, several world maps by Halley, and a copy of Greenville Collins' Great Britain's Coasting Pilot.

Louis Bemaert, agent of the company in Ostend, bought on the Dutch market charts of Hendrick Doncker and also 'een nieuwe generaele wassende paskaert van de gehele werelt by Joannes Loots tot Amsterdam,"' On the Carolus Sextus (1723) German versions of Lastman's 'Bescbryvinge van de kunst der stuer-luyden' and of Gietennaker's 'Vergulden Licbt der Zee-vaert' traveled to Bengal in the private library of Cobbe, the first governor of Banquibazar.

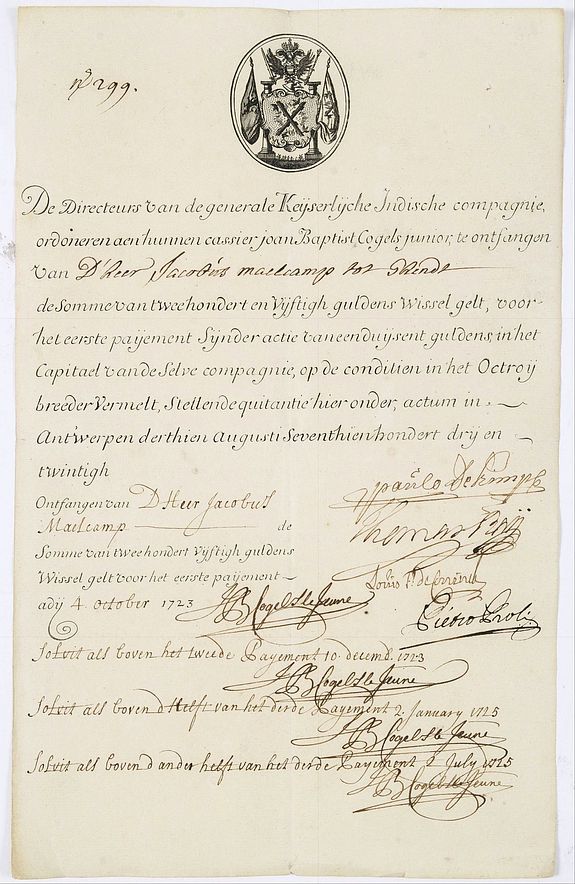

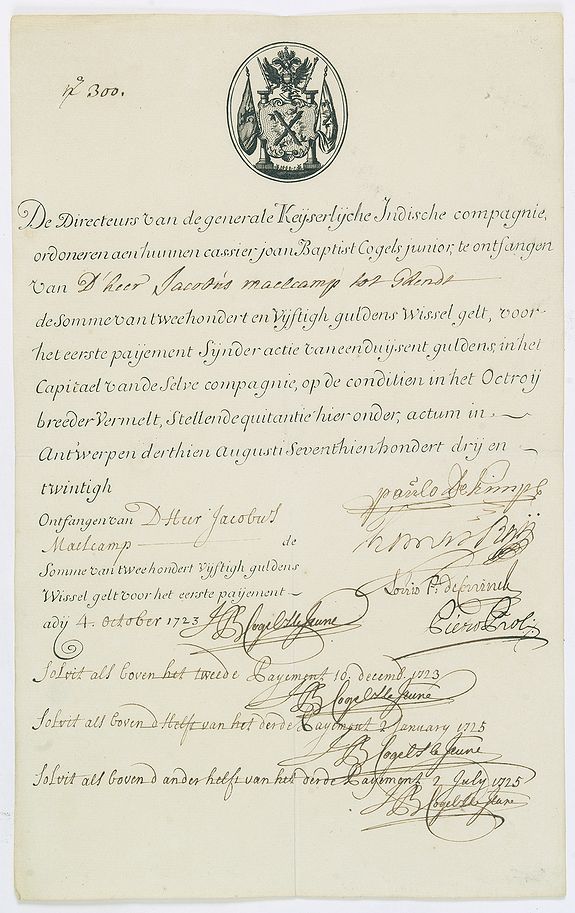

Investors

Among the investors was the Moretus family, heirs of the famous Plantin Printing shop

Jonker Joannes Jacobus Moretus (1690-1757), advocate and publishing printer, was a multi-millionaire, one of the richest men in the Southern Netherlands, if not the wealthiest of them all, had a very active share in the formation of the famous ‘Ostend Company’ and was later one of the promoters of the ‘Trieste and Fiume Company’.

Other major investors was Ferdinand Anthoin Baron de Veecquemans, also from Antwerp who held 100 shares and the family Proli in the same city. Other investors were Melchior Breton (Antwerp),

probably Thomas Hall in London, and other merchants in Antwerp.