The map is an icon of early world maps and has a beautiful aesthetic design. For these reasons, the map illustrates the front and back cover. It is displayed in color as Plate 149, on page 203. of Shirley's monumental carto-bibliography of world maps (

Rodney W. Shirley, The mapping of the world: Early Printed World Maps 1471-1700).

Provence:

This particular item was used on the cover of Rodney Shirley's "The Mapping of the Word" when possessed by Stephanie Hoppen. " Private collection, until date.

The illustration on our site has been photographed behind glass, and some reflection is therefore visible in the image. Shirley's book shows a good image of the map as Plate 149, on page 203 (first edition, 1984).

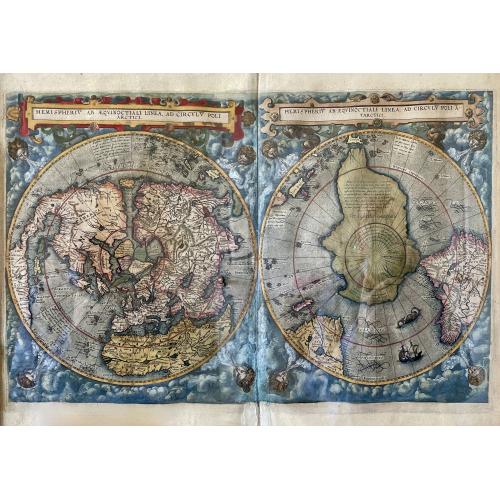

Cornelis de Jode’s map is one of only a few 16th-century maps of the world drawn on a

twin polar hemisphere projection. This map appeared only in the second and

final edition of Gerard and Cornelis de Jode’s Speculum Orbis Terrarum, published in

1593, following the elder De Jode’s death.

The 1593 edition included maps replacing

many in the earlier edition that other cartographers had executed.

These new

maps attempted to keep the Speculum up-to-date with the rapid advances in geographic

knowledge in the late 16th century. Richly annotated with contemporary

geographical knowledge (accurate and myth), much of the geography is largely based

on the Italian maps of the Lafreri School.

The map is based upon the now-lost first edition of Guillaume

Postel’s wall map of the world (1581) and a unique set of globe gores

measuring 2.4 meters x 1.2 meters from circa 1587 known in

one copy in the Bibliotheque Nationale de France, attributed by Marcel

Destombes to

engravers Antoine Wierix and Adrian Collard, who likely made the map for

Cornelis De

Jode (referred to by Destombes as the Antwerp Unicum).

As noted by Rodney Shirley: The map is an interesting adaptation of Guillaume Postel's 1581 world map with some

curious features reminiscent of the large anonymous gores probably published in

Antwerp in about 1587. In both maps we have the same configuration for the northern

coasts - the Gulf of Merosro in North America, the placing of Ter. d Labrador and Nova

Zembla, and the odd junction of the eastern part of Asia with one of the large arctic

masses. Japan is to be found only a few degrees from the west coast of America, and in

the delineation of South Africa and South America, there are further features strongly

suggesting a common source.

One of two

world maps in the 1593 edition of the Speculum Orbis Terrarum, de

Jode’s twin polar view owes much to the world map of French Arabist

scholar Guillaume Postel. Postel, like Mercator, allowed the possibility

of a great south land, though he saw

the Antipodes as part of a greater rethinking of the world along

Biblical lines.

Accordingly, he gave the names of the continents after the sons of Noah associated with them-

Europe became 'Iapetia' (after Japhet), Asia 'Semia' (after Shem) and Africa 'Chamia' or

Cornelis de Jode 'Chamesia' (after Cham).

Postel believed

the south land should be called 'Chasdia', after the son of Cham

(Africa), as he had heard it was populated by dark people. According to

Postel’s account, “For in that part of the coastline that has been

discovered, men were seen of

great blackness.” De Jode’s double hemisphere map follows Postel in

calling the southland Chasdia and the mapping and other annotations are

clearly derived from it.

Most

prominent in capital letters, however, are the letters 'Ter. Australis incognita', thereby giving

Chasdia secondary importance. Large and small islands labeled 'lava maior' and 'lava

minor' also appear on the map, making it clear that neither is associated with the southland.

It is thought that de Jode acquired these source

maps from agents of Venetian and Roman mapmakers at one of the annual gatherings of

the Frankfurt Book Fair.

While de Jode’s Lafreri sources were groundbreaking, as (in sum) the first maps

to, in detail, show all of the world as it was then conceived by Europeans, the present

map naturally shows both the amazing breadth and limitations of contemporary

knowledge.

That factor, and the reality that much

of the world had not yet been explored by Europeans, let alone charted, were

responsible for enduring cartographic misconceptions.

It is worth noting that the fascinating twin polar hemisphere projection excessively attenuated the landforms located near the equator or the

margins of the hemispheres.

Asia

As seen on the left, or northern hemisphere, North

America and Asia are separated by the mythical Strait of Anian, placing Japan very close

to the northwest coast of America. The coastal details in East Asia pre-dating the information disseminated in the works of Rughesi and

Plancius.

The coast of China does not bulge outwards, as it does in reality, but here

sweeps diagonally upward, with no sign of Korea (either island or peninsula). The

Philippines are also not yet shown coherently, as the mapping is still based

on Pigafetta’s rudimentary reports.

While the Malay Peninsula is easily identifiable and notes the Portuguese

trading base of Malacca (secured in 1511), Sumatra is incorrectly identified as Taprobana,

the archaic name for Sri Lanka.

The Indian subcontinent takes on an unfamiliar,

bulbous form, although Sri Lanka correctly appears off of its southeastern tip. The

delineation of the Arabian Peninsula and Africa coasts are quite fine for the time,

emanating from Portuguese sources.

In the Americas, California is named, and the mythical cities of Quivira and

Civola are also labeled. The mapping of Eastern Canada and the American Atlantic

Seaboard is quite rudimentary. Newfoundland is shown, although Labrador is depicted

as an island. The St. Lawrence River is shown to be of an exaggerated breadth, although

Stadcona [Quebec City] and Hochelaga [Montreal], Algonquin towns discovered by

Jacques Cartier, from 1534 to 1541, are noted.

The

northeast coast of North America is highly distorted, featuring a

unique, large bay in the

general area of present-day New York. There is an embryonic Great Lakes

system, and a

large, fictional lake in the northern interior of Canada. East Asia is

shown connected to

one of the four mythical landmasses of the Arctic, and Japan is but a

few degrees from

North America.

Further south towards Florida, the coasts

are bereft of accurate detail, as the map predates John Smith’s mapping of Chesapeake

Bay and New England.

Turning to the southern hemisphere (on the right), a massive Terra Australis

Incognita dominates the projection. The Straits of Magellan separated this apocryphal

continent from South America, a misconception that would remain in place until Le

Maire rounded Cape Horn in 1615.

South America is shown on an extensive projection,

retaining the bulge made famous in the first edition of Ortelius’ map of America. In the

eastern seas, Terra Australis is shown to extend upwards into the eastern reaches of the

Indonesian Archipelago.

De Jode’s map is one of the great icons of map collecting.

The Southern Hemisphere is dominated by a vast Terra Australis Incognita, including Tierra del Fuego and New Guinea.

A Northwest passage through the Arctic region is clearly charted while Japan is shown as a large island at the entrance to Streto de Anian and far too close to America. Magellan's Strait (E strecho de Magellanes) is marked and Tierra del Fuego (C. di Fuego)

is shown to be part of the Southland.

Terra Incognita (Australia)

De Jode’s map shows Ter Australis Incognita as a large island with the notation describing America as a large and admirable island which is regarded now as a fourth continent... (Schilder p.270).

An interesting feature of de Jode's map is the apparent omission of New Guinea. Terra Australis swells up to a large Gilolo instead of New Guinea as is usually portrayed.

De Jode may be referring to New Guinea in his charting of a small island near the south China coast Papua. (Simon Dewez)

While most of the annotations, and all the accompanying text, are in Latin, several terms used are Spanish, including

Islas de Salamon, the Solomon Islands. The representation of New Guinea has significant text, both on the map and on its reverse.

Text appearing on Nova Guinea explains that it was given this name by sailors because the shore was thought to be similar to that of Guinea in Africa. The mapmaker ends by stating that it is not known whether New Guinea is joined to the southern land.

Shirley notes a single copy with

Le Maire's strait added. Also noted is that some copies of de Jode's map

were issued without text on the verso. On the death of Cornelis, the copper plates were sold to Jan Baptist

Vrients, the publisher of Ortelius' atlas, who acquired them merely to

stop their re-issue.

Polar maps were popularized by Dutch mapmakers half a century later.

The questions over what informed these maps go to the heart of debates about

sixteenth-century European charting of the South Pacific. Were these maps purely

speculative, or were they based on sources that no longer survive? And who drew and

engraved them, if not Cornelis?

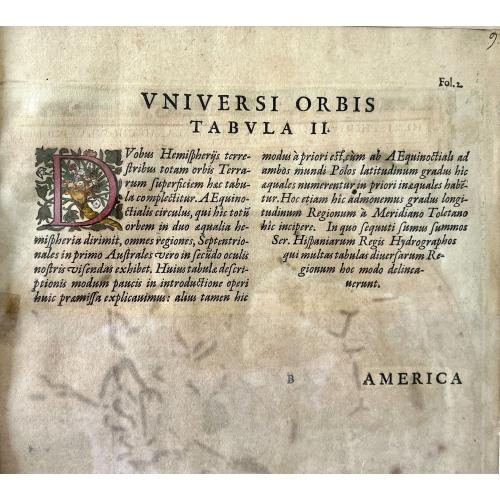

Latin text on the verso, from the 1593 edition of de Jode’s Speculum Orbis

Terrarum. Geographically, the map itself is as striking and unusual as it is in its layout

and design. A possible reason for this is that De Jode sought to differentiate his maps

from those of Abraham Ortelius.

So instead of using the much more common prototype

derived from Mercator’s 1569 wall map of the world (#406) , De Jode, as R.W. Shirley

points out, relied primarily on the more recent 1581 map by Postel and a set of

anonymous gores dating from 1587, resulting in several unusual delineations.

De Jode atlas

In spite of the quality of the De Jode atlas - many of the

De Jode maps are thought to be superior to Ortelius’ - commercially, it was no match.

The lack of success and hence the scarcity of the De Jode atlas are often attributed to his rival’s superior political and business connections; Ortelius could enjoy a license and monopoly for his atlas, whereas De Jode’s efforts to secure a license were fruitless for many years. There are indications that Ortelius actively maneuvered to have De Jode’s application for ecclesiastical and royal imprimaturs delayed until his own expired.

At any rate, the first copies of the Speculum were not sold until 1579, nine years after Ortelius’ work was first published. Also, judging from their name, the De Jodes were Jewish; how this might have affected the fate of their publications has

not been explored by commentators.

It was not until 1593 that the second and final edition appeared under the aegis

of the son, Cornelis, featuring its new maps.

After Cornelis’ death in 1600, the plates for

the Speculum were purchased by Jan Baptist Vrients, who was then publishing Ortelius’

atlas, but there were no later printings of De Jode’s maps. Perhaps Vrients’ purchase was

intended to remove the competition.

Very few of the de Jode plates are known to have been published, without text on the verso, in composite atlases published by Galle as late as 1640. One of such atlases is offered in our gallery catalog (

44442)

Helman, S., “Rethinking the Southern Continent”, Mapping Our World Terra Incognita to Australia, pp. 92-93.; Nordenskiöld, A.E., Facsimile Atlas, p. 95, Plate XLVIII. ; Shirley, R.W., The Mapping of the World, 184 ; Skelton, R.A., 'De Jode Speculum Orbis Terrarum' (Introduction) pp. v-x. ; Wolff, H., America, Early Maps of the New World, p. 83, #101.

The map is an icon of early world maps and has a beautiful aesthetic design. For these reasons, the map illustrates the front and back cover. It is displayed in color as Plate 149, on page 203. of Shirley's monumental carto-bibliography of world maps (Rodney W. Shirley, The mapping of the world: Early Printed World Maps 1471-1700).

The map is an icon of early world maps and has a beautiful aesthetic design. For these reasons, the map illustrates the front and back cover. It is displayed in color as Plate 149, on page 203. of Shirley's monumental carto-bibliography of world maps (Rodney W. Shirley, The mapping of the world: Early Printed World Maps 1471-1700). We provide professional descriptions, condition report and HiBCoR rating (based on 45 years experience in the map business)

We provide professional descriptions, condition report and HiBCoR rating (based on 45 years experience in the map business)![]()