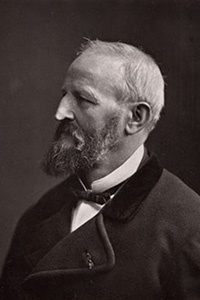

Karl Bodmer

Karl Bodmer, the painter of perhaps the finest of all Plains Indian portraits, was born on February 11, 1809, in Zurich, Switzerland, where he received artistic training from his uncle, landscape painter and engraver Johann Jakob Meyer.

Karl Bodmer, the painter of perhaps the finest of all Plains Indian portraits, was born on February 11, 1809, in Zurich, Switzerland, where he received artistic training from his uncle, landscape painter and engraver Johann Jakob Meyer.

In 1832, naturalist and explorer Prince Maximilian of Wied-Neuwied contracted Bodmer's services for an expedition to North America. Their journey lasted from July 1832 to July 1834, but the most crucial phase began in April 1833, when they set out on a voyage up the Missouri River by steamship and, later, keelboat. During stops at trading posts and encampments, Bodmer composed watercolor portraits of Omaha, Dakota, Assiniboine, Atsina, Mandan, Hidatsa, and Blackfeet chiefs and warriors, but occasionally women and children as well. He also painted village scenes, ceremonies, and a wide variety of landscapes. In August 1833, Maximilian and Bodmer reached Fort McKenzie, near present-day Great Falls, Montana, but faced with menacing warfare among the Blackfeet, they turned back a month later. Spending the harsh winter of 1833–34 in Fort Clark near present-day Bismarck, North Dakota, the two central Europeans established a warm rapport with the Mandans and Hidatsas. Artistically and scientifically, their stay at Fort Clark was the most fruitful part of their journey. The masterful–and ethnographically accurate– watercolor, Interior of a Mandan Earth Lodge, for example, was sketched over a period of several months during their time at Fort Clark.